Six steps to avoid overproduction in your shop floor

If you are a person who is wondering why you need to avoid overproduction in the first place, then there is an another piece of article you need to read before going through this one – 5 reasons why overproduction is harmful. In lean manufacturing we try to get one process to make only what the next process needs and when it needs it. So how can you achieve this in your shop floor? Fortunately you can follow the following guidelines listed below.

Step #1: Produce to your Takt Time

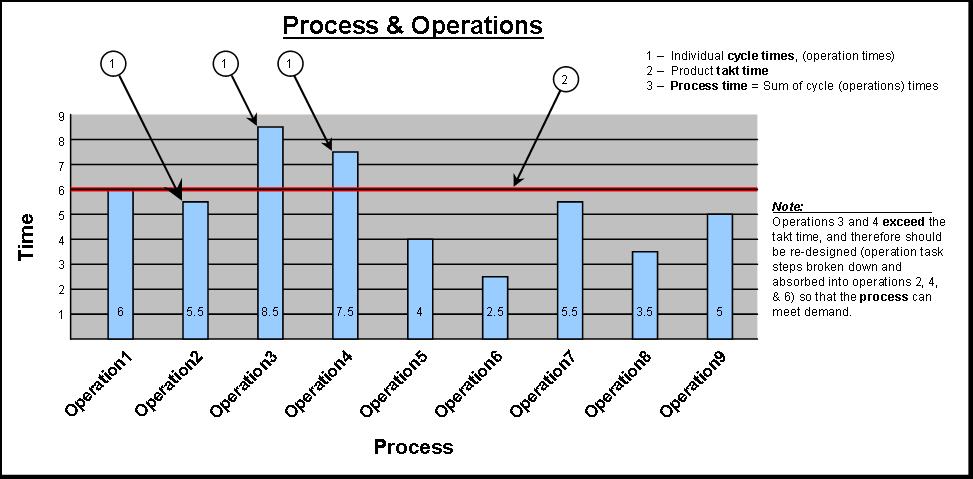

“Takt Time” is how often you should produce one part or product to meet the customer requirements. It is calculated by diving the available working time per day (excluding scheduled breaks) by customer demand rate per day (in units).

This is a reference number that gives you a sense for the rate at which each process should be processing which helps in synchronizing the pace of the entire production.

For example, if any operation has a cycle time equal to the Takt Time (i,e 40 seconds) then the operation can produce 675 parts at the end of one shift. If the cycle time is less than the Takt Time, then the operation has excess capacity and it will lead to overproduction which in turn creates Work-In-Progress (WIP). If the cycle time is greater than the Takt Time, then the operation cannot meet the customer demand and hence it becomes a bottleneck activity. Hence all activities in the production line must have their cycle time below the Takt time in order to achieve the customer demand.

Producing to Takt time sounds simple, but it requires concentrated effort to:

Step #2: Develop continuous flow wherever possible

Continuous flow refers to producing one piece at a time, with each item passed immediately from one process step to the next without stagnation (and many other wastes) in between. It is the most efficient way to produce, and you should use a lot of creativity in trying to achieve it.

However, there are exceptions where you would want to limit the extent of a pure continuous flow because connecting processes in a continuous flow also merge all their lead times and downtimes. A good approach would be, to begin with, a combination of continuous flow and some pull/FIFO system. Then extend the range of continuous flow as process reliability is improved, changeover times are reduced to near zero and smaller in-line equipment is developed.

Step #3: Use supermarkets to control production where continuous flow cannot be extended

Continuous flow is not always possible and batching is necessary at some places in a value stream – when an operation has a faster or slower cycle time, shipping parts from far away like outsourced process and huge lead time. Resist the temptation to schedule these process, as a schedule is only an estimate of what the next process will actually need. Instead, control their production by linking them to their downstream customers via super market-based pull systems. Simply stated, you need to install a pull system where continuous flow is interrupted and the upstream process must still operate in a batch mode.

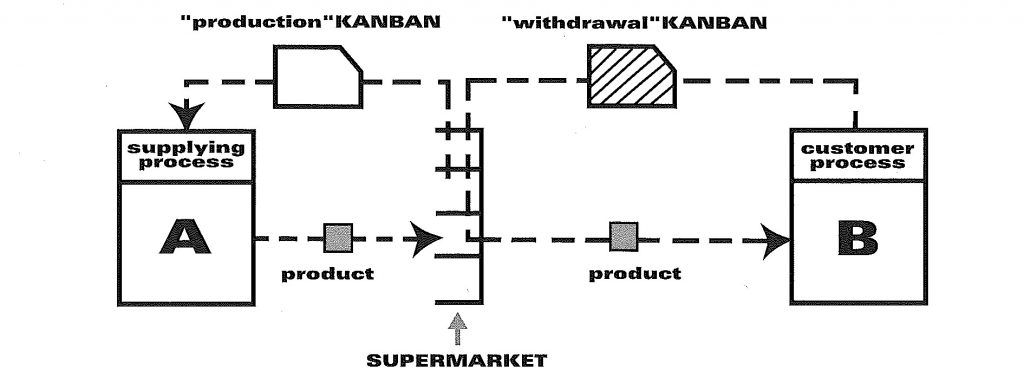

The customer process goes to the supermarket and withdraws what it needs and when it needs it using a withdrawal kanban.

The supply process produces to replenish what was withdrawn using a production kanban.

Purpose – This system controls the production at the supplying process as it produces what is consumed by the next process and no production schedule is required.

A production kanban triggers the production of parts, while a withdrawal kanban is a shopping list that instructs the material handler to get the necessary parts and transfer them.

Step #4: Try to send the customer schedule to only one production process

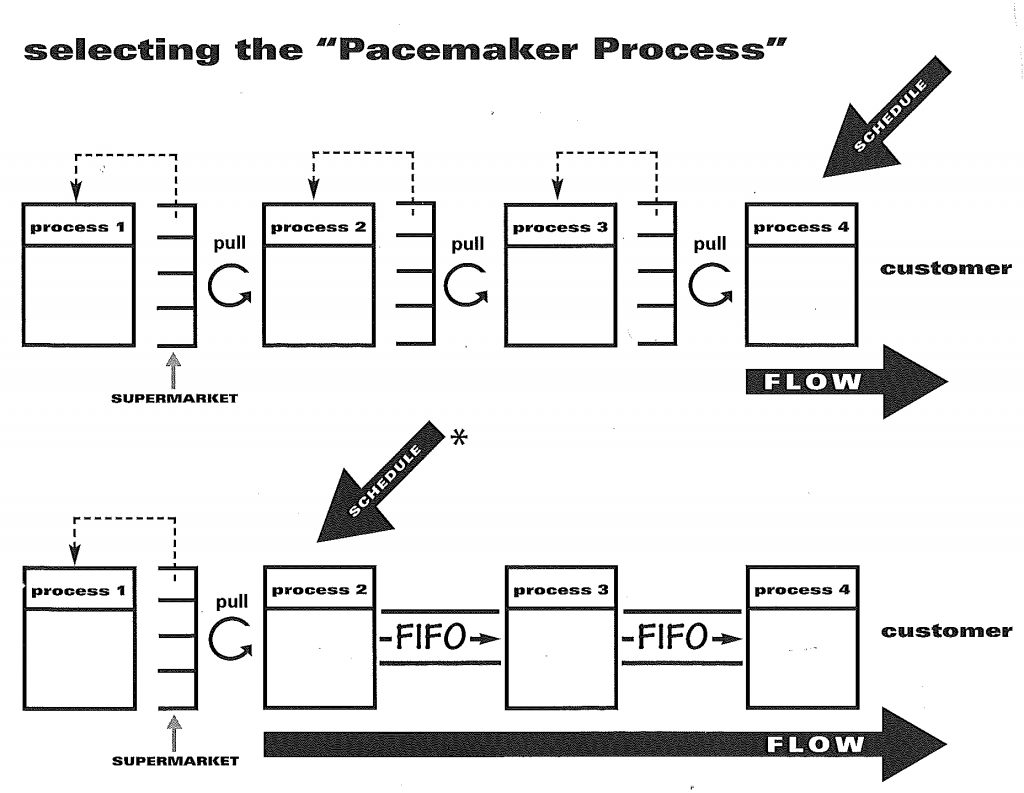

By using super market pull systems, you can can schedule only one point in your downstream value stream. This point is called the pacemaker process, because how you control production at this process sets the pace for all the upstream processes.

The material transfers from the pacemaker process downstream to finished goods need to occur as a flow (without any super markets). Because of this, the pacemaker process is frequently the most downstream continuous-flow process in the door-to-door value stream. On the future state value stream mapping, the pacemaker is the production process that is controlled by the outside customer’s orders.

Step #5: Level the production mix

Most production departments from our observation, find it easier to schedule long runs of one product type to avoid changeovers and hence are required to have more finished goods inventory – in the hope that you will have on-hand what a customer wants. But this makes it difficult to serve customers who want something different from the batch being produced now.

Leveling the product mix means distributing the production of different products evenly over a time period. For example, instead of assembling all the “Type A” products in the morning and all the “Type B” in the afternoon, leveling means alternating repeatedly between smaller batches of “A” and “B”.

The more you level the product mix at the pacemaker process, the more you will be able to respond to different to different customer requirements with a shorter lead time while holding little finished-goods inventory. Your reward is the elimination of large amounts of waste in the value stream.

Step #6: Level the production volume

Releasing large batches of work to the shop floor processes causes several problems:

A good place to start is to regularly release only a small, consistent amount of production instruction (usually between 5-60 minutes worth) at the pacemaker process and simultaneously take away an equal amount of finished goods. This practice is called “Paced withdrawal“.

Companies generally use a load-leveling (or heijunka box) – it has a column of kanban slots for each pitch interval, and a row of kanban slots for each product type. Kanban is placed into the leveling box in the desired mix sequence by product type. The material handler then withdraws those kanban and brings them to the pacemaker process – one at a time, at the pitch increment.

Our ultimate objective is to link all processes – from the final consumer back to the raw material – in a smooth flow without detours that takes the shortest lead time, delivers highest quality and incurs the lowest cost.

Contact us for a consultation on how Hash LLP can help your business with Lean Manufacturing.

+91 9176613965

Join 3500+ Professionals who receive our Weekly Newsletter containing Simple and Practical ideas to help achieve Results in their companies.

Hash Management Services LLP, 2023 © All Rights Reserved